INFREQUENT MOZART

JUPITER KV 551 & BIG CONCERTANT SESTETTO KV 364

LA TEMPESTAD | SILVIA MÁRQUEZ CHULILLA, arreglo, fortepiano y dirección

ARSIS GPD 5244 2013 | DL HU 66/2013

One of the primary functions of music: transcribe to encourage musical exchange. That task is what surprisingly, infrequently, keeps this recording of the Salzburgish master, in whose works – the symphony Jupiter arranged by S. Márquez and A. Clares, and the Sestetto Concertante In an anonymous arrangement (Vienna, 1808) – the classical harmonies of the Mozartian orchestration coexist with the persuasive and enviable texture of this chamber reduction.

The recording, published in the new GPD format (Geaster PenDrive) released by the Arsis label, is completed with the documentary “ Recording Mozart: a New Arrangement of Jupiter Symphony “on the first movement of the symphony Jupiter , directed by the director and photographer Joaquín Clares.

CD CONTENT

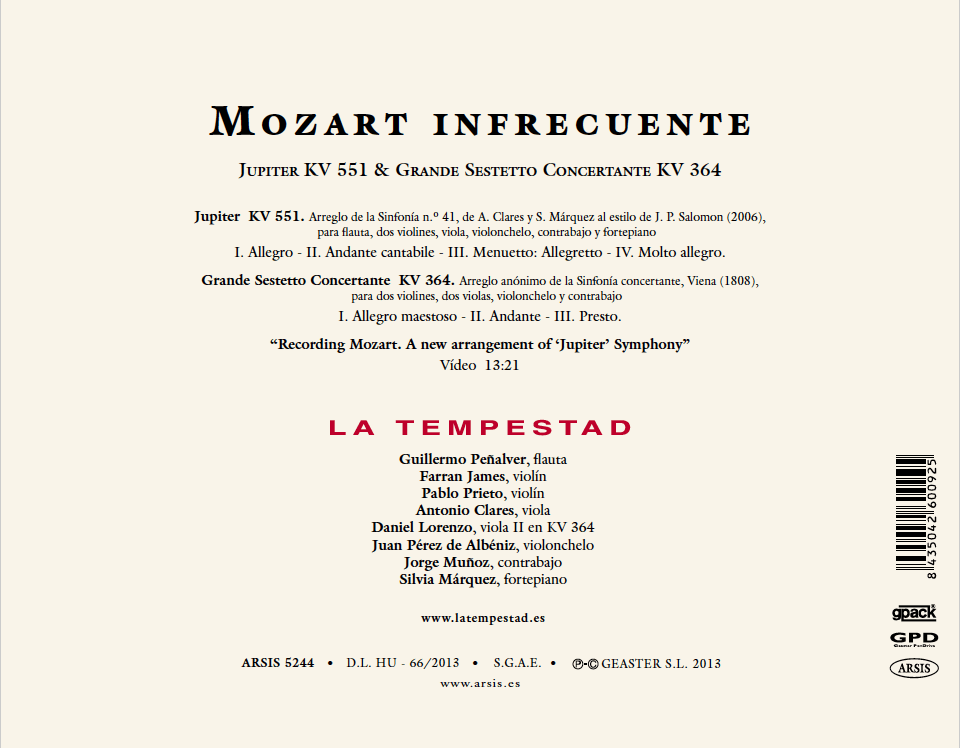

Jupiter KV 551. Arreglo de la Sinfonía n.º 41, de A. Clares y S. Márquez al estilo de J. P. Salomon (2006), para flauta, dos violines, viola, violonchelo, contrabajo y fortepiano

I. Allegro – II. Andante cantabile – III. Menuetto: Allegretto – IV. Molto allegro.

Grande Sestetto Concertante KV 364. Arreglo anónimo de la Sinfonía concertante, Viena (1808), para dos violines, dos violas, violonchelo y contrabajo

I. Allegro maestoso – II. Andante – III. Presto.

“Recording Mozart. A new arrangement of ‘Jupiter’ Symphony”

Vídeo (13:21 min.)

El soporte, consistente en un pendrive de diseño personalizado con capacidad de 4 GB, incluye archivos de audio de alta calidad y en formato mp3, vídeos en alta definición, una galería fotográfica y textos en varios idiomas.

CONTENIDO GPD:

– Grabación en alta defición

– Galería fotográfica

– Documentos html y pdf multimedia

CARACTERÍSTICAS DEL SOPORTE:

– Audio y vídeo en alta definición

– Versiones para dispositivos portátiles

– Más de 7 GB de información

– Calidad Audio WAV 24 bits 48 KHz

– Audio MP3 192kbps

– Vídeo Full HD 1920×1080, MOV y MP4

– Vídeo 720×400 MP4

CD NOTES

I wish we could live until there was nothing left to say in music.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

I. A HUGE ABUNDANCE OF EVENTS

“No artist is during the twenty-four hours of his daily day uninterrupted artist”. With this small and subtle warning prologa Stephan Zweig one of his most famous writings, Star Moments of Humanity. Let there be no doubt, make it clear that all these pinches of history that are told alone, without the need for ornaments, all those events with consequences, which occurred on the most unexpected occasions, were not the result of the genius of their authors… not at least of a lifetime genius. Maybe they grazed her at a very small time in their lives.

Zweig’s life took place between Vienna and Salzburg until the time he went into exile in Brazil fleeing Nazism and Hitler. Fueled by these two cities, it is not uncommon for him to fall under the spell of a character like Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, an illustrious citizen of both. Passionate collector, during the last four decades of his hobby Zweig sought not only characteristic works, but those that could be counted among the achievements of the production of its authors. Mozart was a lifelong fascination for Zweig, whose collection included compositions by the musician from 1784 until his death in 1791, his marriage contract, five letters and eleven autograph manuscripts, including the thematic catalogue of his works from 1784.

How could it not dedicate one of those reflexes that left its mark on humanity to the Salzburg genius? Probably for that: for its genius. “The millions of men who make up a village are necessary for a single genius to be born. It must also take a million hours for a stellar moment of humanity to occur. But when a genius is born in art, it endures through the times.” Zweig was not able to choose, from among Mozart’s many great works, one that would have meant a milestone in history, which stood out among all. Mozart’s prolific and grandiose production in such a short life seemed to want to circumvent the quote from Zweig’s prologue with which we began these notes. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart had no place in that book. His work was not one of those dramatically concentrated moments. It was one, another and another, all of them scattered in a surprisingly brief space of years in the infinite timeline of time.

Stuck with the greatness of so much work, among that “huge abundance of events” that Zweig attributes to the genius, La Tempestad dares a select two of mozartian achievements and present them in compressed format. Two immortal works composed in less than ten years, and among which are a lot of masterpieces: his last three symphonies, five of his mature operas and some of the most beautiful piano sonatas. However, the reduction is not arbitrary, but follows, as we shall see, already traditional methods. The Tempest, in the role of the cook, prepares a dish with “events” that augur a rich aroma: quality raw material (nothing less than the concerto symphony K. 364b and the Symphony “Jupiter” K. 551) and traditional recipe (the transcription). Anyway, genius concentrate. “Apple-converted-space” “”

DIALOGUE AND EXTREMES. CONCERTANT SINFONIA K. 364b

Monsieur Le Gros bought me the concert symphony. He thinks he’s the only one who has it, but he doesn’t: it’s still fresh in my head, and as soon as I get home I’ll write it again, “Apple-converted-space”

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (París, 3 de octubre de 1778)

Too bad he didn’t keep his word, because if he had done so we would not regret today the loss of the concert symphony for oboe, clarinet, horn and bassoon K. 297b, to which Mozart referred in this letter to his father, and which remained in the hands of Le Gros.

Joseph Le Gros, director of the famous Concerts Spirituels deParis, had offered Mozart, who was conducting a tour European between 1777 and 1779, the possibility of using the fortepiano of his house to compose. That’s where he probably wrote the Concerto for flute, harp and orchestra K. 299, which also takes the form of a concert symphony. It was a very vogue genre, which flourished from the 1760s and had a special success in Paris, where composers such as Davaux, Le Duc, Saint-Georges, Gossec, Rigel and Cambini, who wrote more than eighty – cultivated it. It used to consist of two or three movements, the first of which usually in a classic ritornello-sonata shape, while the latter consisted of a rondo. Johann Christian Bach, whom Mozart deeply admired, also composed fifteen concerted symphonies.

However, despite the obvious confidence in his memory, Mozart decided to write a new piece on his return to Salzburg in 1779, which will mean the culmination of this genre: the concerto symphony for violin and viola in E flat major (K. 364/320d). The influences collected in the tour European, which included two important cities: Mannheim and Paris, are added to the experiments carried out so far. In the first he had the privilege of visiting the court orchestra; and in the second he met Joseph Boulogne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges, violinist, composer and conductor very active in those years, who conducted and premiered Haydn’s Parisian symphonies and whose Concerto No. 5 for violin is quoted in the Concertante Symphony of Mozart. The orchestral dynamics of this work reflect the increasingly demanding technical level of the European orchestra of the moment.

If the Flute and Harp Concerto poses a technical challenge for the two soloists, in the concerted symphony K. 364 the two instruments play in a tireless dialogue that imposes itself on the undeniable technical requirement: dialogue between themselves and each of them with the or Questa. The adjective “concertant” makes sense in the most generalized meaning, that of “agreeing, agreeing, deciding together”. Mozart attaches the same importance to both instruments. In fact, the viola part is written in D major instead of my major flat, so the instrument must be tuned a high halftone (scordatura technique) to achieve a brighter loudness. The result is a kind of concentrated sample of Mozart’s character, taken to extremes: the serene joy of the first and third movements (where the two instruments seem to be hunting and playing like children) in the face of drama and drama deep recollection of the second, perhaps one of the saddest movements of all of Mozart’s work, in which many have wanted to see the pain over the recent death of his mother and the disappointment with Aloysia Weber.

GUERRA, MUNDO Y LEY. SINFONÍA «JÚPITER» K. 551

Voi siete un po’ tondo

Mio caro Pompeo

L’usanze del mondo

Andate a studiar

Extract to bacio in mano, K. 541 de W. A. Mozart

Just ten years after that culmination of a genre on horseback between concert and symphony, Mozart writes the last of a series of three symphonies composed in rapid succession, during a summer: on August 10, 1788 the Symphony No. 41 ends , K.551, in C major.

Probably due to the fanfare character of the beginning, the entrepreneur Johann Peter Salomon (as recorded in his diaries Vincent and Mary Novello after a visit to Mozart’s widow, Constance), awarded him the nickname “Jupiter” in the early nineteenth century. A character that would be maintained throughout the movement, were it not for the appearance of a second subject totally contrasting in the exhibition. This theme is but A bacio di mano K. 541, a small opera arithmetic that Mozart had composed for the bass Francesco Albertarelli to premiere within pasquale Anfossi’s Le gelosie fortunate, on 2 June 1788. In the argument, a gallant, man of the world, advises another on the dangers of wooing young ladies,

This recovery of subjects from earlier works was a totally common practice. The freshness of A bacio in mano contrasts with the solidity of the fourth movement, which, at the opposite end, rescues the credemotif motif he had used for the Missa brevis in F major, K. 192. From the loving and earthly lances we move into the divine order. If the elegance of the second movement, above the grim moments, and the minuet, chromatic, take us away from the Olympus of the god Jupiter, the End of this symphony is, continuing with Roman terminology, a cyclopean construction. The five-voice escape is an almost insulting demonstration of compositional mastery, the most virtuous artistic skill, the limits of sound architecture.

As writer and editor Ron Drummond suggests, perhaps Salomon’s title to the symphony is more appropriate in reference to the Finale, no longer because of the appearance of trumpets and fanfare, but because it could be said to encompass in its structure the egalitarian ideas that transformed Europe, for good and evil, during the Enlightenment, for Jupiter, god of light, heaven and time, was also the god of the state, of its welfare and of its laws, and therefore represented its ide condition al,

The “Jupiter” Symphony was the last symphonic work by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Perhaps, preclearly, he considered that finally there was nothing more to say: the struggle, the war character, the world and its customs, the desire, the love, the pain, the religion and the law, the earthly and divine order. everything was there. The exultant final of trumpets and timpani would have been a successful brooch for Mozart’s three-concert series that he planned to perform in Vienna that same autumn. The project failed and we are not aware of the premiere of the Symphony K. 551, but in one way or another it must have transcended, because after the first edition published by André (Offenbach, 1800) arrangements and versions began to circulate that sported that brooch by the more varied scenarios – public and private – to this day,

II. TRANSCRIPTS AND LOANS

The transcription, the basis of the musical exchange as far back as the 17th century (as evidenced by the more than four hundred key versions found at different points in the European geography of more than two hundred fragments of Jean-Baptiste Lully’s operas), was evolving into architects, concept and media.

Until the mid-18th century music served other social interests, whether divine worship or ambient music for food and games in the courts. But little by little musical societies begin to emerge that celebrate their concerts, focused on enjoying only music, in small churches or taverns. With the rise of the bourgeoisie, the commercial exploitation of leisure is becoming more and more economical. And this exploitation also became extensive, among other manifestations, to music. The bourgeoisie, together with the nobility, constituted the most grainy and numerous of the attendees of the opera and public concerts, which were becoming increasingly important in multiple cities. And, along with the professionals, the bourgeois were the best clients of music instruments, as well as the main subscribers of the musical periodicals. Music had definitely ceased to be the exclusive heritage of princes and aristocrats.

Alongside this, the practice of transcription facilitated an exchange of music between composers, hobbyists, countries and instruments that depended on the occasional circumstances, the available instruments and, in many cases, commercial interests. which, above all, allowed to enjoy chamber or orchestral music at home, moving from concert halls to the domestic sphere.

«RIDOTTE IN CONCERTI». MOZART ARREGLISTA

As an exercise I have written the aria Non so d’onde comes, which Bach composed so beautifully. I’ve done it because I know Bach so well and I like the aria so much that I can’t get it out of my head. I wanted to see if he was still able to compose an aria that was nothing like Bach’s. I don’t like it at all.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (Mannheim, 28 de febrero de 1778)

The aria to which Mozart refers in the letter to his father is No. 294 in the catalogue of K’chel. And the Bach he refers to is none other than Johann Christian, “the Bach of London“, which Mozart professed admiration and held in the highest esteem.

Wolfgang transcribed (apparently between the ages of 11 and 15) three sonatas of opus 5 by J. Ch. Bach (published in 1768) that became the Concertos for key K. 107. These concerts, whose instrumental arrangement respected that of J. Ch. Bach himself (2 violins, bass and key), served as a repertoire during his tours when he played in small areas and also to dominate the genre before composing his true first keyboard concerto (K. 175 in D major). The original title of the manuscript read as follows: “Tre Sonate of Sgr. Giovanni Bach ridotte in concerti dal Sgr. Amadeo Wolfgango Mozart“, which attests to the generalization of the term “ridotte“ (reduced) for the practice of the transcript, out of more to less instruments or vice versa, as was the case. The contribution of the Salzburg is more visible in the first movements (the cadence of K. 107/1 is of Mozart himself) than in the latter, where he merely presented the original part of keyboard with a delicate accompaniment by the strings.

Alongside the practice of transcription, Mozart was no stranger to so many other uses common to the time: the frequent use, as we have seen in the “Júpiter“, of own themes written before or taken from other authors; the composition or adaptation of keyboard music accompanied by a violin ad libitum for the domestic enjoyment of fans; or the substitution of movements of a work according to the reaction of the audience once premiered: the orchestral template of Concerto K. 175, composed in Salzburg in 1773, consisted of key, violins I and II, viola, basso, two oboes, two horns, two trumpets and two trumpets and Timpani. But the severe writing of the third movement, composed in the time of study of the counterpoint, should not have pleased the Viennese public very much, so Mozart, without problem, replaced it in 1782 with another totally different inspired movement: the Rond, allegretto grazioso in D major K. 382, adding a flute. “Apple-converted-space” “”

MOZART «ACCOMODATO»

And it is precisely this second version of Concert K. 175 that we find transcribed for two keys, by an anonymous hand, in the Dresden Library, a mine rich in reduced versions of the most important compositions of the moment. The prince elector of the city, Federico Augusto “el Justo“, asked his copyist to manage to enjoy them playing them alongside the palace organist. Among the works «accomodate per due cembali» were compositions by Luigi Boccherini, Joseph Haydn or W. A. Mozart.

As music moved from court meetings and nobles’ halls to the music halls of the bourgeoisie and enlightened middle class, the level of fans and widespread love of music grew exponentially. In the years of the turn of the century, public concerts, already organized by the composer, proliferate, already by the growing number of concert societies. The “gallantstylo“, in front of the complex counterpoint of previous music, leads to the expansion of amateur practice, and the arrangements of famous works proliferate throughout Europe in the early years of the 19th century. Publishers multiply, which see their work increase with publications of varying degrees of difficulty.

Peter Lichtenthal, doctor, composer and musicologist born in Pressburg (present-day Bratislava) in 1780, settled in Milan in 1810, where he remained until his death. There, faced with the impossibility of listening live to Mozart’s orchestral works, he devoted himself with devotion to writing about what he considered the only universal musical genius and to making numerous transcriptions of his work for threesomes, quartets and quintets. In addition to the already famous version of the Requiem, The Symphonys No. 39 and 40 are preserved in the Milan Library in version for string quartet. But No. 41, which he titled “Grand Sinfonia in C colla Fuga“, needed a quintet (two violins, two violas and cello) due to the five voices of the final fugue.

Christopher Hogwood, responsible for the modern edition of this version for string quintet (Edition HH, 2008), lists in the introduction: “The Symphony “Jupiter” was subject to multiple arrangements during the first half of the nineteenth century. In addition to the expected reductions for piano or piano duet, we find the excellent version of Cimador for two violins, two violas, cello, double bass and flute (c. 1805) and the adaptations of Hummel and Clementi for piano with flute, violin and cello; in 1848 William Watts published an adaptation for the same combination of instruments, but with a four-handed piano part. There are some versions for smaller chamber groups: the Finale arranged for string quartet (and transported to D major) can be found in a manuscript of the Prague National Museum (XXVI C 83). ‘

VIENA 1808. UN GRANDE SESTETTO CONCERTANTE

The last ten years of Mozart’s life, his period in Vienna, coincided with a part of history plagued by important events, including the early years of the French Revolution. The ideas of Rousseau, Voltaire, Franklin, Hume, Goethe and Schiller circulated through the halls of a city that, opposite London or Paris, did not have a real concert hall. In these halls, the basis of musical activity, fans of different social strata, including the highest ones, offered concerts and rented the services of famous professionals, such as Mozart himself.

Sigmund Anton Steiner, one of these musicians amateurs, owner since 1803 of the Wiener Chemische Druckerei, was precisely responsible for the publication in 1808 of the Grand Sestetto Concertante, an arrangement of symphony K. 364b. As an unknown author, the Sestetto is written for two violins, two violas and two cellos ( “Violoncello concertante cousin and Violoncello secondo or Contra Basso“). The participation of two viola voices was more than common in Mozart’s symphonic works, including the concert symphony itself.

The first publication of the original version, due to Anton Andro, took place in 1801, and the appearance in Mainz, just a year later, of the first arrangement for piano trio demonstrates the rapid popularity it achieved. If in the orchestral version Mozart attached the same importance to the violin and viola, and subjected them to a constant dialogue, in the Sestetto all have something, much to say. The themes go from one to another voice creating countless reflexes and kaleidoscopic illusions, which,despite embodimenting perhaps a taste closer to that chamber music that Mozart loved so much and enjoyed at the end of his the main problem of the arrangement is the main problem: the fragmentation of sentences into small motives poses a tremendous difficulty in building a movement from start to finish. To this horizontal difficulty is added a second, vertical: the difficult sound balance between two violins, two violas and two bass instruments that are handing out the same material, and whose writing has not been conceived from the beginning as that of a string quartet For example. This is without taking into account the many technical requirements presented by the piece for each and every interpreter.

Perhaps this is why we have today a new arrangement for eight parts, made in 1988 by the cellist Ernst Rosenberger and published in Vienna (of course not!) by the publisher Wolfgang Kiess: the solo voices, violin and viola, remain as in the origi and the winds are integrated into the string sextet, whose sole purpose is to accompany the soloists.

LONDON AND THE “SALOMON” SYMPHONIES

We did not find, however, such problems in the brilliant arrangements of Joseph Haydn’s twelve London Symphonies by Johann Peter Salomon, which have been the germ of this recording.

London housed the first space dedicated exclusively to music, which was none other than the Hanover Square Rooms, a room opened in 1775 by dance master Giovanni Gallini, and where Johann Christian Bach and Carl Friedrich Abel took his successful concert series during the 1770s. In 1776, the well-respected violinist Johann Peter Salomon inaugurated a series of parallel concerts. Years later, learned of the death of Prince Nicholas (in September 1790), Salomon travels to Vienna to try to convince the two great masters, Mozart and Haydn, to move to London. It does so with the second, whose success is total and absolute. His two stays in the English capital constituted, say Haydn himself, the happiest period of his life, during which he will complete the series of his London symphonies, from 99 to 104. However, at the end of the 1795 season, he decided to return to his homeland.

What could go through J. P. Salomon’s mind after his friend Haydn’s decision to leave that city that hailed him? What would the musician and friend think? But what would the restless businessman think of him, seeing his hen leave from the golden eggs? Salomon obviously cannot allow the source of the success of his concerts to be escaped from his hands and, about to leave London, in August 1795, Joseph Haydn signed with the entrepreneur a contract purporting to be beneficial to both ssix first london symphonies. Within a few months he will send the contract from Vienna for the next six, thus obtaining Salomon the right of exploitation of the twelve.

With clear commercial smell, he decides to make a first adaptation of the fortepiano symphonies with the accompaniment ad libitum of a violin or cello. Not too convinced of this first version, insufficient in its texture, Salomon announced in 1798 the publication of a new arrangement, this time for two violins, flute, viola and cello, with accompaniment of fortepiano ad libitum. Now, the richness in detail multiplies and, with a reduced organic, very high degrees of sound fidelity to the original are reached, while it remains a much more accessible formation than the orchestral one. J. P. Salomon’s business activity has often made him forget his musical ability: the arrangements are brilliant, the distribution of papers is meticulously studied. And the possibility of interpreting these arrangements with or without fortepiano was another cunning commercial resource, for although it gained adherellies by leaps and bounds, at the beginning of its expansion it was not an instrument available to all pockets.

In 1780 a simple Broadwood could be purchased for twenty guineas, plus another for the costs of packaging and delivery. A generation later (as is the case today with digital technology), economies of scale and a significant improvement in communications had caused the price to fall to eighteen pounds, including shipping costs. With the advances that builders such as Zumpe, Broadwood or Clementi were applying and the impulse of composers such as Johann Christian Bach or Mozart himself, the fortepiano became the instrument of democratization of music. A student could extract from him pleasant sounds from day one, contrary to what was happening with a violin. When he had learned the rudiments, the pianist could entertain family and friends with dance music or transcriptions of arias from the last operatic success.

III. LA «JÚPITER» FROM LA TEMPESTAD

In the ten years after the publication of Salomon’s arrangements, the table fortwould was taking up positions in London’s houses until it became one more inhabitant. No doubt thanks to this the version of the arrangement of 1808 has come to us with a continuous bass part with which we get a clear idea of the ease with which fans could enjoy this great music… as we have done in La Tempestad during the numerous concerts dedicated to the Salomon Symphonies, in which that continuous bass brought the touch to turn the camera sound into full, orchestral versions. However, after many and many tunings, since our fortepiano, far from being peacefully seated in the heat of a carpet, has traveled with us undergoing innumerable atmospheric changes. Perhaps between one of these tunings came the idea of a new arrangement of the “Jupiter”. Because it was after one of our concerts with Haydn in the beautiful place of Bolea, when Fernando y Pilar, creators of the Arsis label, conceived the idea. In the manner of a Sigmund Steiner, aware of the impossibility of taking an entire orchestra to enjoy the “Jupiter” and having noted the result of Salomon’s arrangements, the solution was there, within reach: to commission a new reduction orchestral score, this time with the same instruments in front of them.

During the four years before Mozart’s death in 1791, offers to take him to London in the successful footsteps of Haydn were numerous, starting, of course, with that of J. P. Salomon. Couldn’t have been. And we loved the idea of a new Salomon-style transcription, convinced that, had the “Jupiter” Symphony closed, the “Jupiter” Symphony would have been one of the entrepreneur’s first goals. We also found it interesting to contribute our grain of sand, an arena of the 21st century, to a practice that we have seen uninterrupted during the eighteenth, nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Why the Salomon model? Because as an excellent musician, entrepreneur and traveller, he surely knew the sextets of Boccherini and Cambini, their sound result and their possible shortcomings, and when transcribing the London Symphonies he was concerned with finding the instrumental combination that best to adapt to the original work with the fewest elements. We, as musicians, play with the advantage of having that path laid out, of knowing the arrangements of Salomon and having tasted them from within, of having the facsimiles. Perhaps all this subtracts some of the freshness that runs through the centuries and comes to us from those nineteenth amateur meetings. But our arrangement of the Jupiter Symphony has been revised and interpreted several times before its final version. Each musician has been able to check whether the writing worked for his instrument, whether or not there was inconsistencies, whether the voice that had just played the same subject had done so differently, whether or not the printed notes corresponded with the logic of a work on the other hand. for a classical musician of today…or if the horns were missing!

How are the parts arranged? Generally speaking, the flute plays the role of different winds in the orchestral score, both in the small dialogues and in the notes held. The violin first stays true to the original, while the second moves from its usual role to forming wind duets with the flute or replacing other instruments. When this happens, the viola, the most versatile instrument in the dessert, assumes the role of the second violin; but it can also become a bassoon, at any given time, or horns, playing war from afar. The double bass adds two functions to the original orchestra part: replacing the cello when it deals with higher voices or percussion in total conjunction with the fortepiano. The latter, which amalgamates the loudness of the ensemble in a surprising way, fulfills exactly the same role as it had in the 1808 London edition of Salomon’s arrangements (a continuous bass already far to the practice of the XVIII, riding between the Baroque cipher and the orchestral reduction). But given the abundance of interesting material in Mozartian orchestration, it adds brushstrokes as small comments of violins or oboes where the rest of the sextet is occupied in essential material, or even reinforces alongside the double bass moments of timbal that print out the percussive character that would otherwise be lacking.

Uncommon today provides the equivalent, in the form of transcription, to an 18th-century record recording wrapped in 21st-century media. It is illustrative to recall that early orchestral recordings posed tremendous balance problems that required an exaggerated reduction in the workforce. Symphonies were often recorded with a single viola, and a double bass performed the functions of an entire string of cellos. Tim Blanning gives a clear example in his book The Triumph of Music: “When in 1914 Arthur Nikisch made the first complete recording of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony with the Berlin Philharmonic was forced to dispense with the double basses and timpani not to play pianissimo or forte‘.

AND THEN, MOZART … INFRUENTIALLY?

Well, yes. Uncommon, for example, because we do want to use double bass, and despite the reduction in staff seems fundamental to achieving the depth of the symphonic works. And not just on Jupiter. The very few recordings of the Large Sestetto Concertante are with two cellos, and we, taking advantage of our usual training and aware of the balance that this decision could entail, we have chosen to the second of the possibilities that the title of the edition offered: “cello or contrabasso”.

Uncommon because, although recent research places Symphony 41 as Mozart’s most performed work by orchestras today, it is not common to hear it in a cameristic format, despite the obvious popularity of all the arrangements to which it has been subjected.

Uncommon because we paid homage to J. P. Salomon following his bill, taking him as a model, acknowledging his good work and artistic background, knowing that his arrangements of Haydn’s symphonies are among the most complete and respectful of this tradition centuries.

Uncommon because, dedicated as we are to historical interpretation, we lacked to enjoy one of the most common customs of the early nineteenth century. It is true that the practice of improvisation as well as experimentation with different instrumental combinations already often appear in the settings of ancient music. But not so the transcription of classical symphonies or opera music of this period, performed by the performers themselves.

And, if we are allowed, uncommon even in an anachronistic way, since two hundred years ago the public expected to listen to new music, pieces that had been written at most ten years before. Would we think today to transcribe the last brilliant premieres of our contemporary composers to take home? “Apple-converted-space” To our view, the current composition would lose its essence if we reduce its instrumentation, if we lose the color set, the different loudnesses.

Precisely the evolution of technology and record media have ended up standardizing the sound of orchestral music, they have sacralized in some way instrumentation, a concept totally unthinkable in the eighteenth century. What wouldn’t Haydn have done about having another orchestra in his esterházy palace? Prepare to listen to the European way of the early nineteenth century, in one of those halls with one of many instrumental combinations that compensated for the reduction of the number with the variety of nuances and the rich individual play, without losing a shred of the invention musical, sound architecture. “Apple-converted-space” “”

A wink to LA TEMPESTAD

As a perfect stranger, Johann Peter Salomon happened to sit at our table day yes and day too. The years spent on his arrangements of Haydn’s London Symphonies made our ignorance more admirer and appreciation. It seems that, once that undertaking is finished, he thought about rounding up the cluster of circumstances that have brought us here, precisely, who gave the name “Jupiter” to Symphony No. 41. Thank you again, Mr. Salomon. It is precisely to us, The Tempest, that comes from pearls. We think it’s a fair decision. Knew. Balanced. In a paradoxical way, and returning the favor to you with a small pun, we think it’s a “solomon” decision.

It is not bad for us, no, that Jupiter, lord of Olympus, king of heaven and earth, of gods and men, who with his gesture was able to shudder at the world, give name to the symphony that causes so many sensations around us.

To achieve his status, Jupiter had to dethrone Cronos, a cruel and tempestuous force of chaos and disorder – go, man, “tempestuous”, under whose mandate being born and beings die without any order (remember that Cronos devours his children). The Romans will call it Saturn. Dethroned his father, Jupiter will definitively ordain the universe, become the divine principle of spirituality, defy the new order of Olympus, establish the basis of relations between all beings. And only on a very, very small scale, and as a Tempest we are, we like to believe those monstrous one-eyed cyclops who, by forging lightning, helped him dethrone Cronos; and enjoy a monumental escape that we imagine as a construction carried out with incessant work of frenetic pace, which, reaching the absolute order, makes us lose track of time…

Silvia Márquez Chulilla

Algezares, last day of the year 2012