MON DIEU, PR-TE-MOI L'OREILLE

MUSIC OF THE 17th FRENCH CENTURY

BANCHETTO MUSICALE, PERE ROS, CATHERINE LASSALLE | SILVIA MÁRQUEZ CHULILLA, clave

ARSIS 4210 2007 | HU 126/2007

Until the king of Navarra Enrique de Borbón did not become Henry IV, king of France (1589), the country could not enjoy the expected appeasement, with the promulgation of the edict of Nantes (1598) and the freedom of worship granted to the Huguenots A period of extraordinary artistic expansion began for France, with two confessions on equal terms. Composers related to the Reformation such as Claude Le Jeune and Eustache du Caurroy agreed to relevant positions.

Psalms, dialogues, fantasies and tombeaux make up the present reading of the fruitful dialogue between two Christian confessions that occurred in France during the 17th century, with an outstanding role for the family of violas da gamba </ em>.

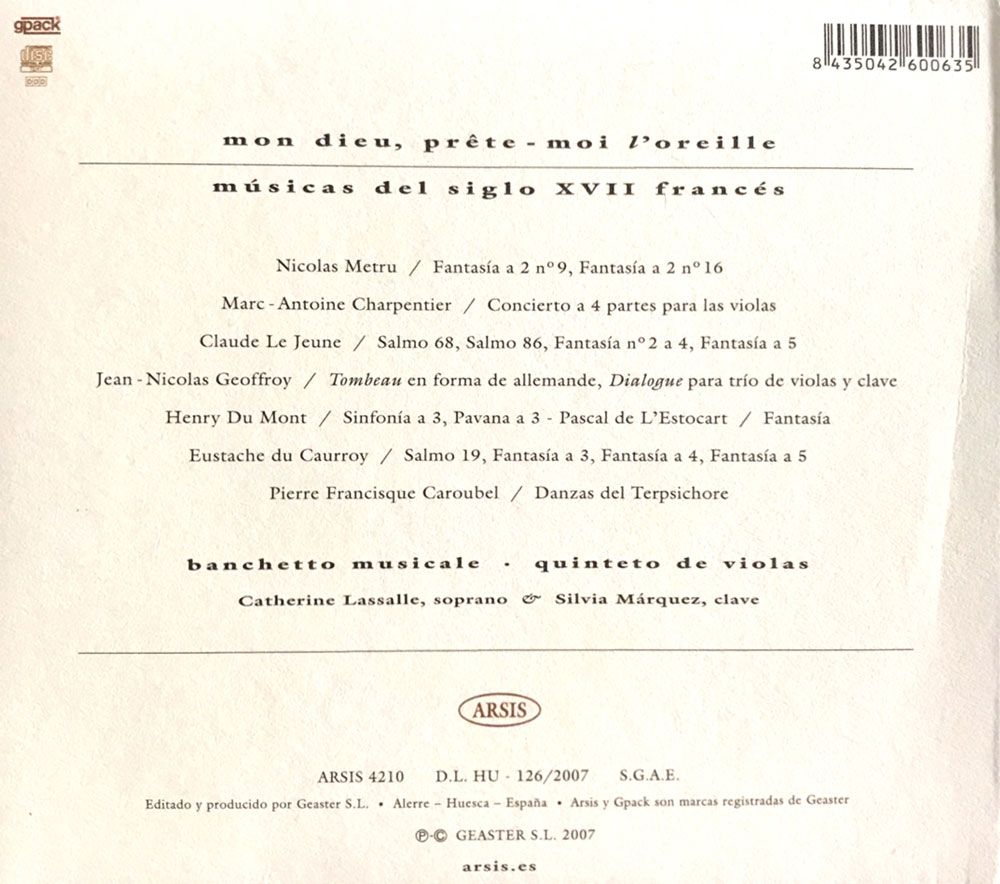

CD CONTENT

02. Henry Du Mont Sinfonía a 3

03. Claude Le Jeune Fantasía n.º 2 a 4

04. Eustache du Caurroy Fantasía a 4 sobre “Ave maris stella”

05. Nicolas Metru Fantasía a 2 n.º 16

06. Eustache du Caurroy Salmo 19 “Les cieux en chacun lieu”. Fantasía a 3

07. Jean-Nicolas Geoffroy Tombeau en forma de allemande

08. Pierre Francisque Caroubel Danzas del “Terpsichore”: Passamezzo – Gallarda – Courante – Volta

09. Claude Le Jeune Fantasía a 5 sobre “Benedicta es caelorum regina”

10. Nicolas Metru Fantasía a 2 nº9

11. Claude Le Jeune Salmo 68 “Que Dieu se montre seulement” | Pascal de L’ Estocart Fantasía

12. Henry Du Mont Pavana a 3

13. Eustache du Caurroy Fantasía a 5 sobre “la sol fa re mi”

14. Marc-Antoine Charpentier Concierto a 4 partes para las violas

15. Eustache du Caurroy Fantasía a 4 sobre “Salve regina”

16. Jean-Nicolas Geoffroy “Dialogue” para trío de violas y clave

CD NOTES

In the same year of the synod, Henry II Valois died a victim of his arrogance, leaving a kingdom divided by the continuous scuffles between the supporters of the Counter-Reformation, led by the Guise, Dukes of Lorena, and the Huguenots, protected by some members of the aristocracy (the princes of Condé and Antonio de Borbón, king of Navarre, among others). Henry II’s sons would also die in tragic circumstances after giving blind sticks against that part of the population prone to embrace the renewing current. However, Catherine of Medici, her mother, always veiled so that they would not be dragged into the counter-reform cause.

Until king of Navarre Henry of Bourbon did not become Henry IV, King of France (1589), the country could not enjoy the expected appeasement, with the promulgation of the edict of Nantes (1598) and the freedom of worship granted to the Huguenots. A period of extraordinary artistic expansion for France began, with the two confessions on an equal footing. Composers related to the Reformation such as Claude Le Jeune and Eustache du Caurroy gained access to prominent positions.

The first, active member of the Académie de Poésie, was appointed chamber composer of the king and, following in the footsteps of Philippe Jambe de Fer and Claude Goudimel, put in polyphony the psaltery of Calvin. His 6-voice version of Psalm 86 Mon Dieu, pr’te-moi l’oreille (No. 1) opens the present reading of some important examples of the fruitful dialogue between two Christian confessions that occurred in France during the 17th century, with a prominent role for the family of violas da gamba.

Two fantasies edited posthumously, one to 4 voices on a simple first-tone motif (No. 3) and five the other, based on a 7th-tone Gregorian melisma recalling the mottete Josquin des Prés wrote a century ago for 6 voices on the same melisma (No. 9) , along with the 4-voice version of Psalm 68 “Que Dieu se montre seulement” (choral melody “O Mensch bewein dein S’nde groo”) complete le Jeune’s contribution. Another version of the same psalm due to Pascal de l’Estocart, Calvin’s country musician who knew how to maintain good relations with both sides, has been included in No. 11.

Eustache du Caurroy, appointed sous-maétre and chamber composer of the King in 1595, enjoyed enormous respect from his contemporaries and successors. The fantasies about Gregorian chants (of Catholic origin) Salve regina (No. 15) and Ave maris stella (No. 4), both for 4 voices, as well as one to 5 voices on the, sun, fa, re, mi (No. 13, evoking a mass of the same title of Josquin des Prés based on a meli sma del kyrie “Cunctipotens genitor Deus”), they coexist in their work with other melodies on melodies of the Huguenot Psyllone, such as that of Psalm 19, “Les cieux en chacun lieu” (No. 6).

Away were the horrors of the night of St. Bartholomew’s (1572), when Charles IX’s soldiers passed the Protestant people through arms. The monarch died a few years later, unable to get rid of such heavy ballast, and his brother Henry III would die murdered by a supposed Catholic friar in 1589. Even Henry IV, under whose reign prospects of peace and prosperity were opened, was stabbed by a fanatic in 1610.

Shortly before the second assassination of Pierre Francisque Caroubel, violinist of the king’s chamber, he traveled to the Court of Brunsvic (Germany) carrying with him the compositions of dances that he used to perform in the French Court. The Terpsichore, a collection of music collected and published in 1612 by Michael Praetorius, contine 82 of these compositions (No. 8).

During the regency of Maria de Medici (widow of Henry IV and mother of Louis XIII) the music had a formidable flourish. The queen was said to take ennemond Gautier’s lute classes, being unsuccessfully emulated by the Cardinal of Richelieu, who wanted nothing less than his sovereign.

Music teachers Nicholas Metru (who is said to have been by Jean Baptiste Lully – No. 5 and 10 -) and the Belgian Henry du Mont, composer of the chapel and chamber since 1672 and harpsichordist of the queen (No. 2 and 12) , were able to develop their new musical forms thanks to the active organization of the music chapels, the schoenías, the Chamber of the Court and the new great fashion of the opera (in 1647 a Orpheus of Luigi Rossi, expressly commissioned by the Cardinal Marenzio).

Under Louis XIV he reached the music an unequaled summit. Within the pléyade of composers, Marc-Antoine Charpentier (who enjoyed the support of a descendant of those Guise who opposed Henry IV so much, by arms and diplomacy, and to a lesser extent, Jean-Nicolas Geoffroy (organist in Paris and Perpignan) composed relentlessly for the great liturgies of the Court and of the Church.

The latter left a beautiful testimony in a much appreciated way at the time, that of the tombeaux, sound epitaphs dedicated to some character, although they may not explicitly bear the name of a dedicatee (as is the case of piece No. 7, written for key and evocative of the touch of the dead in the passage titled carillon). Almost another epitaph, but this time from the fenscient world of the family of violas da gamba, is the beautiful suite of Marc Antoine Charpentier entitled Concert a quatre parties pour les violes (No. 14), written a few years before Louis XIV undid the walked by his grandfather, when in 1685 the edict of Nantes was revoked, after which the Huguenot centers of worship were crumbled, liturgical meetings were banned and the Catholic baptism of the children was imposed, causing a mass emigration of Huguenots to other host countries. The dialogue pour les violes et le clavessin (No. 16) symbolizes, with its continuous rhetorical games and daring harmonies, an invitation to remake the bridges of dialogue.

Thanks to the invaluable help provided by Jean-Luc Salique, Lisette Aubert-Millaret, Claire Gautrot-Gobillard and Juan Carlos Asensio, we have been able to gather all the materials necessary for the present anthology of French music of the seventeenth century.

Pere Ros

junio de 2007