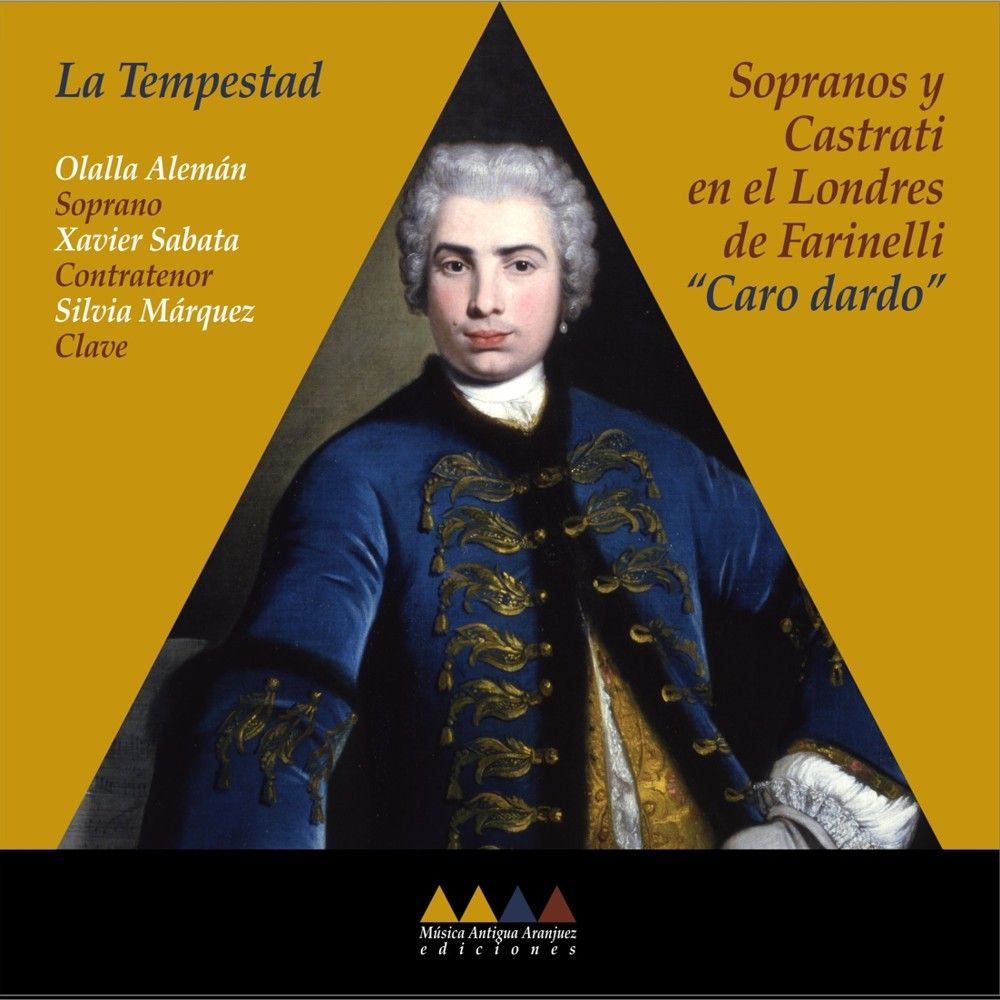

EXPENSIVE DARDO

SOPRANOS AND CASTRATI IN FARINELLI'S LONDON

OLALLA ALEMÁN - XAVIER SABATA - LA TEMPESTAD | SILVIA MÁRQUEZ CHULILLA, clave y dirección

MÚSICA ANTIGUA ARANJUEZ 006 2007 | DL M-14948-2007

Under the label of Caro dart , music is collected here that alludes to the baroque topic of love and death, Eros and Thanatos: the arrow of love ties the soul with its sweet wound and causes it to die in the arms of the to be loved. This is a record recorded in June 2006 at the Royal Palace of Aranjuez, precisely where the prodigious voice of the Farinelli castrate relieved the melancholy of the first Hispanic Bourbon.

The void in the English music scene after the death of Henry Purcell was filled by Italian opera, which flooded the English stages during the first half of the 18th century. The voices of acute tessellation dominated Baroque opera almost completely, so the most relevant male roles used to be entrusted to castrati and female sopranos, who rivaled trills, twitter and coloratures.

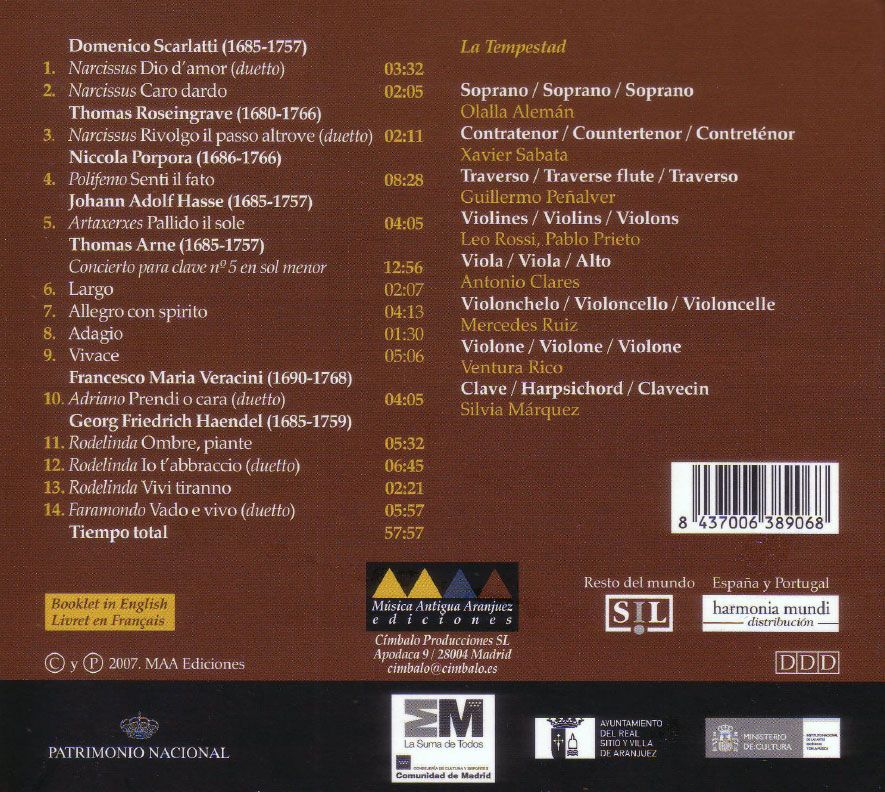

CD CONTENT

01. Narcissus Dio d’amor (duetto)

02. Narcissus Caro Dardo

Thomas Roseingrave (1688 – 1776)

03. Narcissus Rivolgo il passo altrove (duetto)

Niccola Porpora (1686 – 1768)

04. Polifemo Senti il fato

Johann Adolf Hasse (1699 – 1783)

05. Artaxerxes Pallido il sole

Thomas Arne (1710 – 1778)

Concierto para clave nº 5 en Sol menor

06. Largo

07. Allegro con spirito

08. Adagio

09. Vivace

Francesco Maria Veracini (1690 – 1768)

10. Adriano Prendi o Cara (duetto)

Georg Friedrich Haendel (1685 – 1759)

11. Rodelinda Ombre, piante

12. Rodelinda Io t’abbraccio (duetto)

13. Rodelinda Vivi tiranno

14. Faramondo Vado e vivo (duetto)

CD NOTES

The musical ties between England and Italy were intense: to continue on the path of dialectics, it is said (although the event is only recounted in the biography of Haendel published in 1760 by Mainwaring) that around 1708 or 1709 D. Scarlatti and G.F. Haendel is they faced in Rome in a keyboard-friendly competition, from which Haendel emerged victorious to the organ, while Scarlatti made it to the key. But it is in the weekly concerts organized by Cardinal Pietro Ottoboni that D. SCARLATTI meet virtuosos and composers such as Corelli and Thomas Roseingrave, who played a decisive role in the dissemination of Scarlatti’s music by England and Ireland. This is how we find in the London stages of 1720 his opera Narcissus, actually a revised version of Amor d’un ombra e gelosia d’un aura (Rome, 1714), with several musical numbers composed by Roseingrave himself, and presumably represented under Haendel’s direction, then director of the Royal Academy of Music. In the selection edited by I. Walsh and I. Hare (“Songs in the New Opera call’d Narcissus as they are perform’d at the King’s Theatre for the Royal Academy (…) with the additional songs composed by Mr. Roseingrave.”) they appear Dio d’amor and Caro dart: both introduce the theme of the arrow that hurts the character with love, immersed from that moment in a bittersweet mixture of love and pain, kisses and blood. Far from that state of intoxication, Th. ROSEINGRAVE play with a double artifice in Rivolgo il passo altrove: on the one hand, Narcisso oscillates between decision and weakness, impetus and fragility, embodied moods of a highly descriptive mode in music; on the other hand, Ecco’s responses, which repeat the last part of Narcissus’s words, are chosen so that in the mouth of one and the other they have different meanings: altrove / ove? (to the other side/where?); udir-/i-(I’ll hear/say); m’innamoro/moro (I fall in love/die); fuggo della foresta/ resta (run of the forest / stay)… The fact that the sopranos who premiered Narcissus were the “Sig.ra Durastanti and Mrs. A. Robinson” shows that even in 1720 there was some hope for English singers (even though Mrs. Robinson spoke fluent Italian and never sang in English operas). From then on the panorama darkens with the arrival of virtuosos such as the castrate Senesino or the soprano Francesca Cuzzoni.

The figure of the castrati was for centuries a reason for success and envy, struggles and insults, bigotry and admiration. For a time, due to the prohibition imposed on women from singing in churches and theaters, talented children were selected for castration, with the aim of avoiding voice change and retaining their extraordinary thesis. By virtue of the operation to which they had been subjected, on the English scene of the 1920s and 18th centuries, the agility and power of famous castrati such as Carlo Broschi “Farinelli”, Senesino, Caffarelli and Bernacchi, among others, caused a furore among the public and quarrels among the sopranos of the time (the Cuzzonio the Bordoni, “The Rival Queens” ), among the halls in vogue (King’s Theatre, Covent Garden), among the producers, the companies (the Academy, the Nobility Opera) and even the composers ( Haendel, Porpora, Hasse) who based their success and part of the expressive resources of their operas on the quality of these voices. The struggle for primacy went beyond the musical fact: outside the scene Farinelli’s charismandy was confronted with Senesino’s upheaw and insolence; or the Englishman defended himself against the Italian that Haendel used with increasing fondness. However, given the few people who spoke it, the plot would not have been successful were it not for the programs that were purchased at the entrance of the theaters, and in which the English translation and the cast appeared.

During this period the conventions of Italian opera were established in London as in other countries. The narrated events occurred during long recitatives and the arias served as a prolonged expression of feelings that had been left in the air at the end of these recitatives. The script or script had to be complex enough to allow the main characters to sing various arias showing varying feelings, and it was this that really delighting the audience. Even the number of arias each character sang was set according to their status. In the words of the Venetian playwright and libretist Goldoni:

The three main characters of the drama must sing five arias each; (…) The author of the lyrics must provide the musician with different shadows that form the chiaroscuro of the music (…). You should distribute with equal caution the bravura, action, lower, and minuet and hoby.

We offer, on the advice of Goldoni, an aria of bravura to each of our singers, thus leaving the duel served. Both are written in E flat, a tone reserved for moments of sublime seriousness, bleak thoughts, love until death (human or divine love… In the case of N. PORPORA, Neapolitan, like D. Scarlatti, his mastery of adapting the Italian language to music was recognized in his time, and in 1734, after working in cities such as Naples, Rome, Venice, Dresden and Vienna, he was invited to form a opera company (The Opera of Nobility) to rival Haendel’s, and whose cast included the best Italian singers of the time. His version of Polifemo, based on the story of the nymph Galatea, his love for Acis and the love of the Polylifemo cyclops for her (with libretto by Paolo Rolli), premiered at the King’s Theatre in February 1735, with the Cuzzoni, Senesino, Farinelli (for whom Porpora writes the role of Acis, protagonist of Senti il Fato), Sgra. Bertolli, Sgra. Segatti and Sgr. Montagnana. The entire opera is a waste of virtuosity for the main characters. The custom was to offer a castoratethe role of the hero, but it was not uncommon to hear these roles in the mouth of female sopranos, an option we have preferred this time. Moreover, J.A. HASSE abandons his work as a tenor at the Hamburg Opera to travel to Italy, where he lived for three years in Venice, Bologna, Florence and Rome, before settling in 1724 in Naples. There he studied with Porpora and A. Scarlatti. Farinelli, also a student of Porpora, sings his first compositions, from which Hasse receives orders incessantly. Artaxerxes, premiered in Venice in 1730, opens the door to Europe and the court of Dresden, allowing her to marry the Bordoni, a famous soprano already throughout Europe and, of course, on the London stages. This fact, coupled with Porpora’s direction at the Opera of Nobility, makes possible the performance of Artaxerses in London in the 1734-35 season, in which both Farinelli and the Cuzzoni reprised their roles. Senesino was the new castrato (after Nicolini’s death in 1732) for Pallido il Sole: the writing, the lyrics intensified with daring chords and the tone of E flat on a constant murmur of semi-corks in the violins were to produce real shudders in the audience. Like many of the arias of the time, it was written in the form of Da Capo, which allowed the singers of the time (and ours) to offer difficult ornamentations with which the public eagerly awaited the transformation of the original vocal line (despite the recommendations of moderation by P.F. Tosi, castratewithdrawn, in his treatise on singing). Again broadcast in a compilation by the editor J.Walsh, Pallido il Sole became one of the most famous arias later sung by Farinelli, although it was not written for him.

Half an hour before the curtain rose, the orchestra began to enliven the audience with music planned for it. Similarly there were pieces for the interacts and for the end. From the 1930s onones these musics were announced in the newspapers, and the concerti grosside Geminiani, Corelli or Haendel were performed so often that everyone knew them. Sometimes they were announcedconcertosinterpreted by famous soloists or virtuosos, which served as an attraction. As an intermission and as a break for the singers we present on this album the Concerto no 5 of Th. ARNE. The Public Advertiser february 5, 1751 announced a new concerto “composed by Mr. Arne and performed by Master Arne”. The interpreter and attraction at the same time was the son of Th. Arne, Michael, a precocious virtuoso. Although they were not published in the composer’s lifetime (despite the original plan to publish it by subscription), the title of the parties, published in 1793, offers the possibility of performing his six concertos to the organ, key or fortepiano. The brilliant figuration and ornamentation of No. 5 invites interpretation to the key, while hand crosses, certain harmonic twists and the writing of the last movement make it inevitable to think of the Scarlattian influence. In our version we adapted the instrumentation to the group (traverso instead of oboes): the orchestral template of Covent Garden shows that, as in many European orchestras of the time, the same musician alternated between the flute and the oboe.

The success of the musical part of a performance depended not only on the composer conducting from the key, but on the presence of a good concertino at the head of the orchestra (and absolutely responsible in the case of the composer’s absence). It is in that position that we found F. M. VERACINI in London as far back as 1714. Twenty years later he would return as an opera composer. Prendi or Cara is one of the arias published by Walsh, selected from the opera Adriano, released in 1735 and where again we see in the cast sig.r Senesino and the Sig.ra Bertolli (protagonists of this duetto), together with this duetto), together with this duetto), together with this duetto), together with this duetto), together with this duetto), together with this duetto), together with this duetto), together with this duetto), together with this duetto), together with this duetto), together with this duetto), together with this duetto), together with this duetto), together with this duetto), together with this duetto), together with this duetto), together with this duetto), together with this duetto), together with this duetto), together with this duetto), together with this duetto), together with this duetto), Farinelli and the Cuzzoni. The following announcement appears on the cover of the edition: “Note. Where these arias are sold you can also find Apollo’s Feast in four volumes, containing the favorite songs of all of Mr. Haendel’s operas”. Needless to say, G.F. HAENDEL far surpassed that of his contemporaries, and publishers did not miss an opportunity to capitalize on it. The vocal lines and accompaniments of Haendel’s arias accentuated the emotional depth of conventional lyrics and situations, and his music was conceived in a dramatic and even descriptive way. Rodelinda was Haendel’s third masterpiece in less than a year. Released in 1725, it represents one of the highest points of his career, and was an immediate success. Ombre, piant reflects the feeling of pain and anguish at the husband’s grave, accentuated by the supports and suspensions of the voice, and by the echo of the flute as a lament. Lo t’abbraccio shows the pain of the separation between Rodelinda (the Cuzzoni) and Bertarido (Senesino), and Enlive Tyranny represents triumph over the enemy and the greatness of saving him. If the disc started with Cupid’s arrow and left us with clouds and threats before the interlude, Vado and alive (Faramondo, 1738) serves as a final snap and opens a beam of light behind these grim arias.

The arias that make up the program cover the period between 1720 (Farinelli’s first public appearance) and 1738 (after its withdrawal from London theatres, and after achieving fame in all European settings), and form a pasticcio (a method very much in vogue in the representations of the second half of the XVIII) that represents what the London viewers had accepted as a new style of opera: albeit with detractors, Italian opera, sung entirely and with the emphasis on arias and quality of the singers, had defeated the one that only 30 years ago, with spoken dialogue, masquerades, dances and stage effects delighting the English… in his own language.

Silvia Márquez Chulilla