SCARLATTI

VENEZIA 1742: BASSO CONTINUO SONATAS

LA TEMPESTAD | SILVIA MÁRQUEZ CHULILLA, arreglos y dirección

IBS CLASSICAL IBS212018 | DL GR 1295-2018

Entre el más de medio millar de sonatas de indiscutible lenguaje clavecinístico, de gran riqueza armónica, brillantes, líricas o virtuosísticas, asoma tímidamente un pequeño conjunto que poco tiene que ver con el resto: se trata de las sonatas K. 73, K. 77, K. 79/80, K. 81 y K. 88-91, escritas con una sencilla línea de tiple y un bajo parcamente cifrado.

Imaginar cómo suena el énfasis rítmico de las sonatas de Scarlatti en otros instrumentos, más allá del clave u otros teclados, puede resultar una tentación difícil de vencer. Lo fue para aquellos que tuvieron en sus manos alguno de los manuscritos recién salidos del horno en el siglo XVIII y lo ha sido también para Silvia Márquez, que las presenta aquí en arreglo camerístico para La Tempestad.

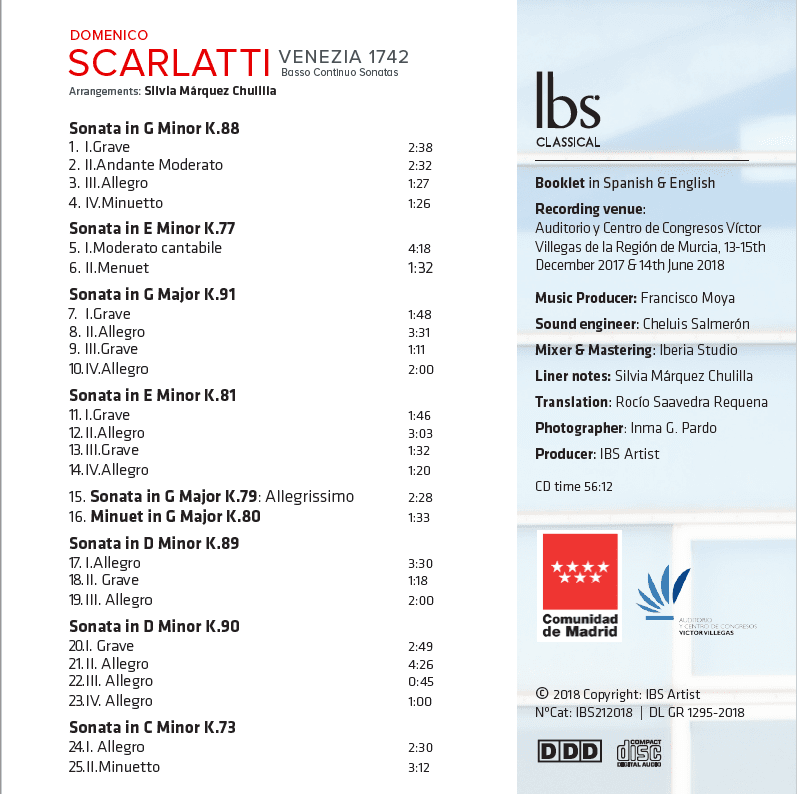

CONTENIDO DEL CD

1. I.Grave 2:38

2. II.Andante Moderato 2:32

3. III.Allegro 1:27

4. IV.Minuetto 1:26

Sonata in E Minor K.77

5. I.Moderato cantabile 4:18

6. II.Menuet 1:32

Sonata in G Major K.91

7. I.Grave 1:48

8. II.Allegro 3:31

9. III.Grave 1:11

10. IV.Allegro 2:00

Sonata in E Minor K.81

11. I.Grave 1:46

12. II.Allegro 3:03

13. III.Grave 1:32

14. IV.Allegro 1:20

15. Sonata in G Major K.79: Allegrissimo 2:28

16. Minuet in G Major K.80 1:33

Sonata in D Minor K.89

17. I.Allegro 3:30

18. II. Grave 1:18

19. III. Allegro 2:00

Sonata in D Minor K.90

20. I. Grave 2:49

21. II. Allegro 4:26

22. III. Allegro 0:45

23. IV. Allegro 1:00

Sonata in C Minor K.73

24. I. Allegro 2:30

25. II.Minuetto

World Premiere Recording

NOTAS AL CD

UN VIRAJE RADICAL

Yo, don Domingo Escarlati, vecino de esta Corte y natural de la ziudad de Nápoles (…).

El ilustre vecino de la madrileña calle Ancha de San Bernardo que firmaba así en 1741 la promesa de dote a favor de su segunda esposa –la gaditana Anastasia Jiménez– no era otro queDomenico Scarlatti, maestro de música de María Bárbara de Braganza. Tan preciado cargo se le había encomendado a principios de la década de 1720, cuando Domenico se traslada a Portugal como maestro de capilla de la corte del rey João V. Los años al servicio de la infanta portuguesa y después también de su esposo, Fernando VI, le permitieron llevar una vida holgada hasta su muerte, aunque con seguridad mucho más retirada que lo que había conocido en su etapa italiana.

En efecto,Nápoles constituía en el siglo XVIII uno de los principales centros musicales de Europa y Alessandro Scarlatti era uno de los más prolíficos y reconocidos compositores de ópera del momento. Hijo de este, Domenico creció en un ambiente familiar estrechamente ligado a la ópera y el teatro: cantantes, compositores y empresarios teatrales convivían al abrigo de la arrolladora personalidad del cabeza de familia que, por supuesto, hizo todo lo que estaba en sus manos para asegurar a su hijo un puesto fijo. Razón, entre otras, por la que se trasladó con él a Roma y por la que dos años después envió a Domenico al ducado de Venecia, donde permaneció cuatro años. Allí tuvo ocasión de entrar en contacto con el famoso castrato Nicolò Grimaldi “Niccolini” y con afamados compositores como Francesco Gasparini, Antonio Vivaldi o Georg Friedrich Haendel. Sin embargo, no es su periodo veneciano el que inspira el título de este disco; de hecho, poco se sabe de esos años, y la experiencia no debió de ser tan fructuosa como se esperaba, ya que Domenico decide regresar a la ciudad de los papas en 1708.

En Roma, Domenico asistía a las accademie poetico-musicali, encuentros musicales patrocinados por el Cardenal Ottoboni donde se reunían los mejores músicos que pasaban por la ciudad. Allí tuvo ocasión de conocer a virtuosos y compositores como Arcangelo Corelli o Thomas Roseingrave –que desempeñará un papel decisivo en la difusión de la obra de Scarlatti años después–. Fue en esos conciertos donde entró en contacto con la familia real portuguesa y también donde el joven Domenico se vio compitiendo al teclado con su estricto contemporáneo Haendel (con el ya conocido resultado: el sajón logró la victoria al órgano mientras que el napolitano se impuso al clave). En definitiva, un exigente entorno social y cultural –en ocasiones muy competitivo– que quizás no encajaba con la personalidad de Domenico y que respondía más bien a las aspiraciones paternas.

Por eso, Portugal debió de suponer para Domenico una especie de liberación creativa –culminada por la muerte de Alessandro en 1725–. El paso de una península a la otra marca algo más que un mero distanciamiento geográfico: un giro radical en su producción. Como maestro de capilla de la corte portuguesa compuso al inicio algunas óperas e incluso tuvo ocasión de realizar otro viaje a Roma en el que continuó conociendo a personalidades como Johann Joaquim Quantz o el gran castrato Carlo Broschi, “Farinelli”. Pero su papel como preceptor de la joven princesa María Bárbara le descubre un ámbito privado en el que expresarse sin necesidad de grandes públicos ni escenarios y un género –el de la sonata para tecla–, que ya no abandonaría nunca. Eso sí, si en algo podían coincidir padre e hijo –el uno en la música vocal, el otro en la instrumental– es en la condición de prolíficos: Alessandro escribió un centenar de óperas y unas 750 cantatas; Domenico, cerca de 600 sonatas.

Tras la boda de María Bárbara con el futuro Fernando VI en 1729, el napolitano se traslada a Sevilla, donde Felipe V se había instalado por motivos de salud. Scarlatti, cuya actividad alternaba clases de clavicémbalo y recitales de clave o de cámara, pudo ya percibir allí la animadversión que la reina, Isabel de Farnesio, mostraba hacia el príncipe. Isabel no soportaba la idea de que el heredero al trono no fuera hijo suyo sino de la primera esposa de Felipe V y hacía lo posible por relegar a los príncipes a un segundo plano. El regreso de la corte a Madrid en 1733 no mejoró la situación. Al contrario: en 1737 Isabel hizo venir a Farinelli con el cometido de dirigir las óperas y proyectar en el resto de Europa el esplendor de la corte madrileña. Al parecer intentó provocar el enfrentamiento entre la nueva estrella y Scarlatti, juego al que no se prestó el famoso castrato. La amistad entre ambos italianos quedó reflejada en diversos cuadros y grabados que los muestran paseando o tocando juntos en una barca, clave incluido. Es un misterio y resulta difícil admitir que no nos haya llegado mucha más música vocal de la pluma de Scarlatti teniendo en cuenta su formación, tan ligada a la ópera, y la presencia tan cercana de la voz más famosa en la Europa del momento.

En cualquier caso, estar dedicado al clave tantos años le permitió explorar las posibilidades expresivas de un instrumento que, por otra parte, iba creciendo y evolucionando. A la corte llegaban las últimas novedades y también los primeros pianos. En este contexto, ventajoso pero reservado al pequeño círculo real, fueron compuestas las sonatas de Scarlatti.

ALGUNAS SONATAS… DIFERENTES

Pero ¡atención! Entre ese más de medio millar de sonatas de indiscutible lenguaje clavecinístico, de gran riqueza armónica, brillantes, líricas o virtuosísticas, asoma tímidamente un pequeño conjunto que poco tiene que ver con el resto: se trata principalmente de las sonatas K. 73, K. 77, K. 79/80, K. 81 y K. 88-91.

Gráficamente, la escritura es lo primero que llama la atención, pues dichas sonatas presentan una línea de tiple y unbajo parcialmente cifrado, lo cual hace pensar que estaban destinadas a un instrumento melódico con acompañamiento del bajo continuo. De hecho, se suelen interpretar al violín o a la flauta, e incluso a la mandolina, decisión esta última que nada debe extrañar. En los años 80 se descubrió en la Biblioteca del Arsenal de París un manuscrito con una colección de música italiana del siglo XVIII, época en la que la mandolina era un instrumento tremendamente popular. La indicación “Sonatino per Mandolino e Cembalo del sign. Scarlatti” al principio de una de las sonatas (precisamente una de las nuestras, la K. 89), con partes separadas para tiple y bajo, justifica históricamente esta práctica. La idea de que estas piezas no fueron concebidas para tecla viene corroborada por la presencia, en sonatas como la K. 88 y K. 91, de ciertos acordes puntuales inabarcables con una mano al clave y sin embargo posibles al violín o a la mandolina (aunque no precisamente naturales, lo cual podría también deberse al hecho de que Domenico no fuera violinista; no sería la única música que escribiera incómoda para los instrumentos de cuerda).

La otra gran diferencia de este conjunto con respecto al corpus más conocido de las sonatas es su estructura formal: frente a la forma binaria en un movimiento, estas sonatas oscilan entre los dos y los cuatro movimientos, alternando lentos y rápidos en un equilibrio que se acerca en ocasiones a la sonata da chiesa (como es el caso de la sonata K. 88, con una fuga en el segundo movimiento) y por lo general a la sonata da camera establecida por Corelli. En ellas encontramos danzas como el minueto y la gavota, y muchos de los allegros son en realidad gigas.

Por último, el lenguaje que recorre estas sonatas está lejos de obedecer al tópico de la cadencia frigia o las reminiscencias de la música popular y la guitarra. Perfecto conocedor del contrapunto, Scarlatti rompería sus reglas una y otra vez en las sonatas posteriores, introduciendo elementos como las quintas paralelas o los cruces de manos, y tomando direcciones prácticamente imposibles de anticipar. Sin embargo, las sonatas que recoge esta grabación responden al barroco más ortodoxo y obedecen estrictamente las normas de la composición desde el bajo continuo. ¿Servirían, quizás, a un propósito pedagógico? ¿Formarían parte de las enseñanzas que recibió la joven princesa María Bárbara? ¿O se acomodarían fácilmente a aquellas interpretaciones de cámara de las que disfrutaban los príncipes?

MANUSCRITOS AL ROJO VIVO

Sea cual fuere su función, el estilo de estas sonatas ha llevado a los estudiosos a calificarlas de “arcaicas” dentro de la producción scarlattiana, sin siquiera conocer la fecha de composición, asunto todavía por descifrar.

He aquí otro de los misterios que acompañan a la figura de Domenico Scarlatti: el paradero de sus manuscritos autógrafos, pues a día de hoy no se conserva ninguno. Las primeras y únicas sonatas que vieron la luz en vida del autor lo hicieron gracias a aquel joven Thomas Roseingrave, que con anterioridad había difundido las primeras óperas de Scarlatti en Inglaterra tras sus encuentros en Roma, responsable ahora de la primera edición de los treinta Essercizi per gravicembalo (1738-1739). Así, cuando Domenico muere en Madrid el 23 de julio de 1757 deja detrás una ingente colección de manuscritos que no habían tenido ocasión de llegar al público y que únicamente habían sido disfrutados en un cerrado entorno privado en España o Portugal.

Por fortuna la reina, probablemente muy consciente del valor de la colección que ya atesoraba y de que el genio continuaba creando, decide entre 1752 to 1757 hacer un providencial encargo: trece volúmenes de sonatas de Scarlatti fueron meticulosamente copiados en gran formato. A estas series de sonatas, espaciadas y ricamente decoradas con tinta de colores, se unieron dos volúmenes copiados en 1742 y 1749 (este incluso con ilustraciones en oro para los títulos y anotaciones). Los quince volúmenes estaban elegantemente encuadernados en piel de Marruecos, con los escudos de armas de España y Portugal en relieve de oro.

Un tesoro que en 1835 fue adquirido por la Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana de Venecia. Paradójicamente, esa Venecia que no consiguió retener o emplear a Scarlatti en vida alberga desde entonces la fuente más importante de su legado. Los quince volúmenes, conocidos como “los manuscritos de Venecia”, recogen 496 sonatas. Los numerados como XIV y XV son en realidad los más antiguos, por lo que el volumen XIV de la colección de Venecia es el copiado en 1742 y el que contiene las sonatas de la presente grabación. Otros quince volúmenes que fueron copiados entre 1752 y 1757, en parte por el mismo copista y duplicando prácticamente los anteriores, constituyen la segunda fuente principal, conservada en la Biblioteca Palatina de Parma. Pero en ellos no aparecen ni nuestras sonatas con bajo cifrado ni las ricas decoraciones en color.

“Venezia 1742” significa, por tanto, un conjunto único y distinto. Y lo que pretendemos en esta grabación es convertir en vivo sonido esa riqueza del manuscrito que no hacía sino transmitir la admiración real. Venecia, la ciudad de los canales que reflejan coloridas fachadas y de los interiores vestidos de Tintoretto, Tiziano y Veronés, alberga también joyas scarlattianas adornadas con sugerente tinta roja. Rojos los títulos y, curiosamente, las cifras de esos bajos que representan, en definitiva, el sustento de este disco.

DE CHARLES AVISON A LA TEMPESTAD

Imaginar cómo suena el énfasis rítmico de las sonatas de Scarlatti en otros instrumentos, más allá del clave u otros teclados, puede resultar una tentación difícil de vencer. Lo fue para nosotros y lo debió de ser, también, para aquellos que tuvieron en sus manos alguno de los manuscritos calientes, recién salidos del horno, en el siglo XVIII.

Porque, llegados a este punto, aflora un nuevo misterio: ¿qué pasó con todos aquellos conocidos que Scarlatti tuvo oportunidad de encontrar en Roma o Venecia? ¿Mantuvo contactos con otros compositores europeos, como Thomas Roseingrave, una vez al servicio de la corte en Madrid? ¿Qué fue de los puentes tendidos a Londres? ¿Cómo es posible que algunas de las sonatas que hoy solo se conservan en el manuscrito de Venecia corrieran por Inglaterra ya en una fecha tan temprana como 1744 (supuestamente incluso antes)?

Lo cierto es que Charles Avison, músico que poco se alejó de su ciudad natal, Newcastle-upon- Tyne, se sumó pronto a los admiradores y defensores de Domenico Scarlatti en Inglaterra. Y en 1744 publicó doce conciertos para cuerda tomando como fuentes la edición de las sonatas realizada por Roseingrave y “algunos movimientos de un manuscrito”: ¡precisamente movimientos de las sonatas K. 81, K. 88, K. 89 y K. 90! (Al parecer Francesco Geminiani pudo tener que ver con la llegada de estos manuscritos a territorio inglés).

“Twelve Concerto’s [sic] in Seven Parts for Four Violins, one Alto Viola, a Violoncello, & a Thorough Bass, done from two Books of Lessons for the Harpsichord. Composed by Sigr. Domenico Scarlatti with additional Slow Movements from Manuscript Solo Pieces, by the same Author. Dedicated to Mrs. Bowes […] Printed for the Author, by Joseph Barber in Newcastle, and Sold by the musick Shops in town.”

Desconocemos si Domenico llegó a saber de estos Concerti o si dio su aprobación, pero el procedimiento seguido por Avison demostraba una absoluta libertad: cada concierto tenía cuatro movimientos; Avison reunía algunas sonatas bipartitas en la misma tonalidad e intercalaba alguno de los movimientos de las sonatas con continuo del manuscrito, adaptando la tonalidad o los tempi originales si era necesario, y escribiendo él tanto las partes instrumentales requeridas como algunos de los movimientos. Con estos arreglos, Avison expandió la fama de Scarlatti por todo el norte de Inglaterra y tradujo el lenguaje clavecinístico a uno de los géneros más en boga en el momento: el concerto grosso.

De vuelta al siglo XXI, los arreglos que aquí presenta La Tempestad se ciñen a la concepción original de las piezas, respetando el número y orden de los movimientos dentro de las sonatas, tal y como aparecen en el manuscrito. Como curiosidad, por ejemplo, cabe decir que la sonata K. 79 carece de cifrado en el bajo, mientras que la K. 80 sí lo tiene; pero ambas aparecen emparejadas como una única sonata (Sonata XLV) en el manuscrito de Venecia.

Los procedimientos que se han seguido son sencillos: reparto de la línea de tiple entre dos instrumentos y escritura de las líneas intermedias (K. 73, K. 80, K. 88, K. 91), en ocasiones tomando como modelo algunos de los recursos violinísticos utilizados por Avison (K. 90); a la inversa, dejando a las cuerdas la realización del continuo mientras la mano derecha del clave continúa con su línea original (es el caso del trío en el Minuetto de la K. 73); distribución de las partes, es decir, una mera instrumentación propiciada por la superposición de motivos cortos y respuestas breves (K. 81, fuga de la K. 88, K. 89). Para dar variedad al conjunto algunas de las sonatas se han reservado a la flauta, conservando así la concepción original y más habitual (tiple y bajo continuo), pero con la línea superior profusamente ornamentada (K. 77, elaborada por nuestro flautista, Guillermo Peñalver). Todo ello, combinado con un mayor o menor juego en la realización del continuo, nos ha permitido completar el dibujo de las dos líneas originales, colorearlo a nuestro antojo y, sobre todo, ampliar nuestro repertorio camerístico incluyendo el nombre de uno de los pilares principales de la música ibérica del siglo XVIII: Domenico Scarlatti.

Sonatas, clave, princesas… inevitable recordar fugazmente el principio de la famosa Sonatina de Rubén Darío:

“La princesa está triste… ¿qué tendrá la princesa?

Los suspiros se escapan de su boca de fresa,

que ha perdido la risa, que ha perdido el color.

La princesa está pálida en su silla de oro;

está mudo el teclado de su clave sonoro,

y en un vaso, olvidada, se desmaya una flor.”

Nada más lejos. Nuestra princesa sacó el mayor provecho posible de su clave, aprendió, disfrutó, escuchó al genio, cuidó su obra y nos la legó. Música brillante y luminosa como la tinta roja acompañó a María Bárbara de Braganza toda una vida.

Silvia Márquez Chulilla